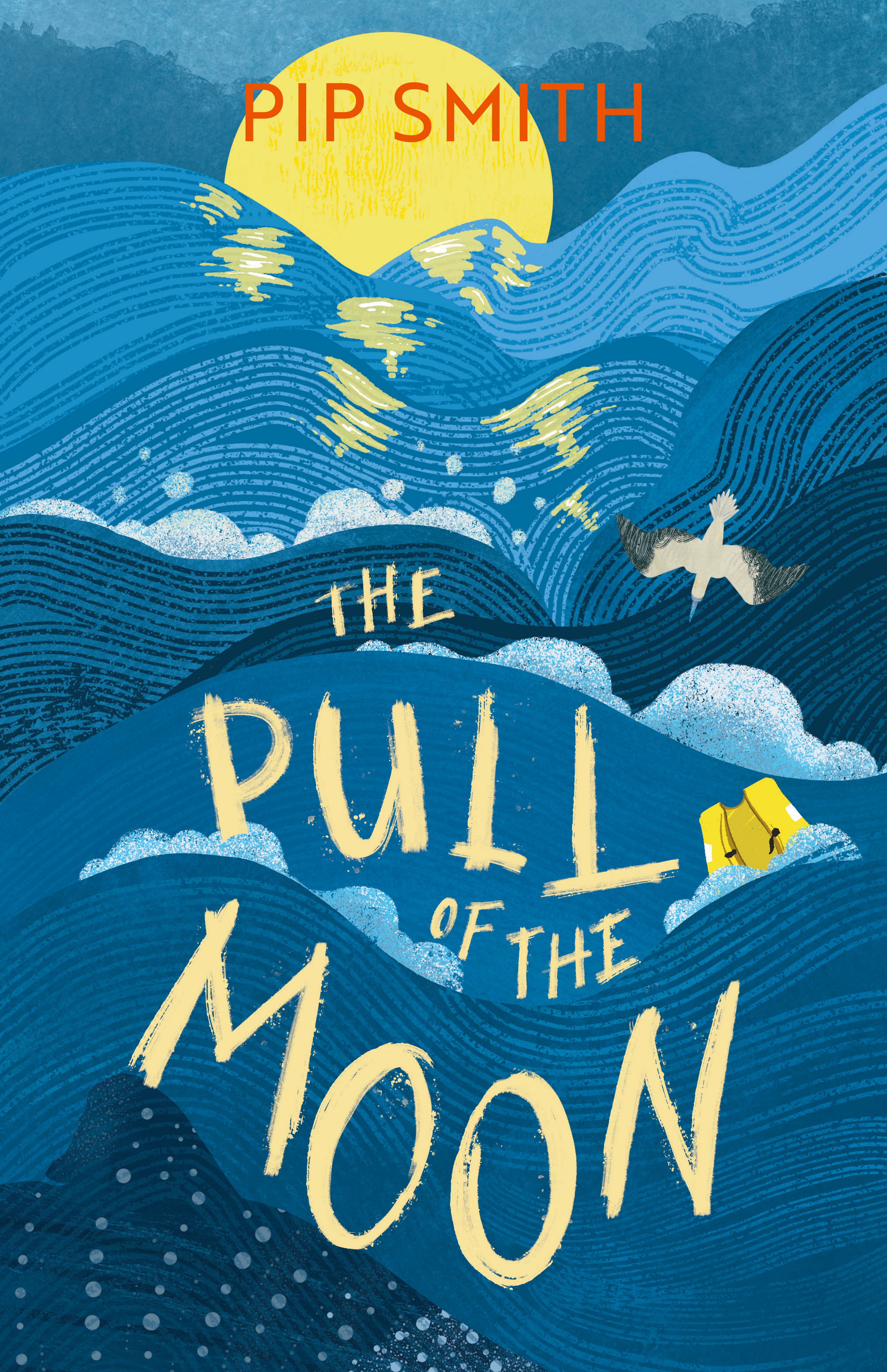

The pull of the moon by Pip Smith

Many would associate Christmas Island with the location of a refugee detention centre, but Pip Smith’s novel begins with the search for the endangered pipistrelle, a microbat that Coralie’s mother, Hannah, tries desperately to track down and protect. Christmas Island is also host to a massive annual red crab migration through forests, across roads, even through buildings, in their determination to reach the sea. The island is a lush natural environment that Coralie can roam freely, though perhaps a little more cautiously through the jungle, reputed to be haunted by ghosts. The export of phosphate and the import of refugees just carries on quietly in the background. That is, until the day an overladen wooden boat is tossed by the waves against the cliffs, smashing bodies on the rocks.

With the changing phases of the moon, the narrative voice changes from that of Coralie to Ali and his family fleeing from Iran, buying passage on a boat from Indonesia to Australia. Their story vividly brings to life the plight of the refugee and the reasons they might desperately seek safety. There is a section in the book where a woman furiously rants against Immigration interviewers, with a speech that should shock every reader into reassessing Australia’s refugee policy. It is a speech that passionately advocates for better understanding and compassion.

Each section of the novel takes place during a different phase of the moon, emphasizing the pull of the natural world and all the creatures within it. At times the perspective is that of a bird riding the thermals in the sky, looking down on the island in the sea. In her author’s note, Smith writes that an Afghan man once told her that he missed the ‘tiny lives of the plum trees’ and her realisation that each blossom was ‘a whole life, a whole world’. This is the feeling that flows through her book, of all the different lives that ebb and flow, lives saved and lives lost, the crabs that make it to the sea and the crabs that are crushed, the refugee who miraculously leaps to safety, and the refugee who is drowned.

At thirteen, Coralie is going through a difficult time, her friends have moved on, the pipistrelles disappear, her mother leaves on prolonged fieldtrips, her father seems at a loss, and then she witnesses the horror of the wrecked refugee boat. She fiercely wants to believe the boy Ali has survived and determines to find him. Smith absolutely captures the feelings of the distraught teenager, the angry words flung at a parent, the passion that drives her, and then the loneliness and confusion when she starts to doubt herself.

The writing style is beautiful, concise and vivid, so many dramatic moments captured so perfectly, moments like the father with his beard ‘speckled with the mince that the stove had spat at his face’ and the mother stabbing her spaghetti with a fork and twisting it ‘slowly, like a knife in the back’.

It is a moving story that young teenagers could read and readily empathise with Coralie and Ali; but the themes of the decline of the natural world and how the moon could just be the earth ‘but in the future, when all the trees and animals have gone’, refugees and imprisonment, the cruelty of chance, all would make it a thought-provoking read for adults as well. Highly recommended for teenagers and adults. Teacher's notes are available.

Themes: Christmas Island, Environment, Biodiversity, Refugees, Trauma.

Helen Eddy