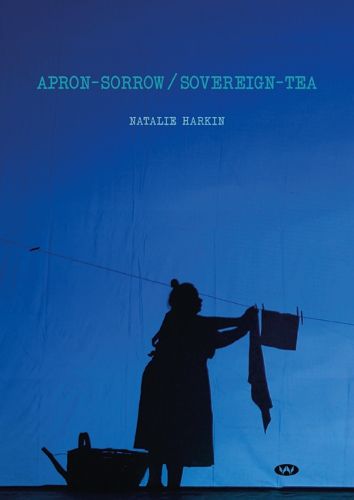

Apron - Sorrow/Sovereign -Tea by Natalie Harkin

Natalie Harkin’s book follows the 2021 exhibition exploring Aboriginal women’s domestic labour and servitude. The book itself is beautiful with images of the leadlight triptych depicting women washing and cleaning, as well as other images of silhouetted figures hanging out clothes or drinking tea, and the iconic clothesline pegged out with white aprons and printed stories on tea towels.

But the history presented is far from beautiful. Drawing on research of State records it tells the story of girls taken from their parents and groomed for servitude. It is a hidden history; legal advice through the Attorney-General’s Department is required for every search of the records, and access to files considered ‘sensitive’ is blocked or the files themselves redacted. The colonial archive speaks of the desirability of taking children as young as three years of age, despite recognition that the mothers were ‘very fond of their children’. The rationale was that at three years of age, the heaviest burden of caring for them was passed; the children were attractive and still malleable, without habits and customs too entrenched.

For decades the lives of Aboriginal people were closely controlled and monitored. Can you imagine being subjected to regular inspection by ‘State Ladies’ who could check the contents of your cupboards and conduct physical body examinations of the children? Heaven forbid if 'just before noon, the beds in your home were still unmade'. It would have been a formidable challenge to stand against such authority. But resist, many did. In fact there was a 1923 petition to the governor 'GIVE US OUR CHILDREN', and in the archive there are many letters pleading for their return.

The ‘memory stories’ of the girls themselves are gathered in the second section of the book, domestic stories shared by mothers and grandmothers, hardworking women of resilience, warmth and dignity, stories of survival, with a philosophy of 'it is what it is', but always retaining a strong sense of family and of Country.

The hardest section to read is the collection of archival records created by state and institution administrators. They are so lacking in empathy, or any kind of humanity, coldly making judgements on skin shade, build and suitability for work, refusing personal requests in 'the best interests of the girls', admonishing one for refusing to give up her baby, rejecting family requests to reunite for Christmas or for a short holiday after years of unpaid work.

In all, this is a treasure of a book, attractively presented, and an important record of a history too easily hidden and forgotten. For there to be reconciliation there needs to be truth-telling, and this book is a part of that. It concludes with a Harkin’s heart-felt poem, ‘I see you I will never let you go’, a moving tribute to women who are ‘blood memory’, ‘sovereign’, ‘radiant’, ‘songline’, ‘love’.

Themes: Stolen generations, Aboriginal women, Domestic servitude, Control.

Helen Eddy