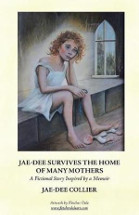

Jae-Dee survives the home of many mothers by Jae-Dee Collier

Balboa Press, 2018. ISBN: 9781504315692.

(Age: 14+) Highly recommended. Jae-Dee's sad story of abandonment to

an Adelaide orphanage as a three year old in the 1950s is

fictionalised, told from the point of view of the child. So it's the

child's voice we hear as she struggles to make sense of the world

she finds herself in, longing for love but always receiving

rejection and humiliation from Sster, as the children call the nun

in charge. Sster Grace couldn't be more removed from the idea of

grace; she is harsh and cruel, beats the children in her charge and

subjects them to cruel taunting and humiliation. Jae-Dee is a

bed-wetter, and as a three year old has to drag her sheets to the

laundry, hand-wash them, and drag the clothes basket to the

clothesline.

Jae-Dee has beautiful memories of her parents, a handsome couple

gliding across the ballroom. She longs to be with them. But whilst

they are good intentioned, they are a fragile couple, her mother ill

and teetering on depression and her father too fond of the drink.

Nevertheless, for Jae-Dee it is the love of her mother and father

that she constantly craves - she desperately wants to be reunited

with them and with her younger sisters. It is the abuse and lack of

love in the orphanage that becomes the most damaging experience.

Collier clearly writes from her memories; she captures exactly how a

three year old struggles with the stairs, planting both feet on each

step, and then how she skips to keep up with the nun's quick stride

along the corridor. We share in the child's love of warm sweet food

like rice pudding, and her detestation of boiled vegetables. And we

empathise with her humiliation and embarrassment as she wakes each

morning in a wet bed. From time to time, Collier adds a comment as

an adult, reminding us this all really happened - children who were

so in need of love and care, were kept in the most cold and uncaring

environment, in an institution that was supposed to stand for love

and charity.

At the end of the book, Collier includes the transcript of the Prime

Minister's 2009 apology to the Forgotten Australians and former

child migrants; a recognition and regret for the experiences of

children who suffered neglect and abuse in orphanages, and a

reminder that the protection of children is a sacred duty. It is to

be hoped that in writing her story, Collier finds release from some

of the memories, and strength in knowing she is a survivor.

Helen Eddy